Panel 1

Maria Gabriella Andrisani, Fiorenzo Fumanti, Mauro Lucarini, Agata Patanè, Monica Serra

The indicator considers extraction sites for first-category minerals, as classified by current regulations, excluding fluid energy sources and mineral and/or thermal water springs, present in the national territory from 1870 to the present. It serves a dual purpose: identifying potential mineral deposits still exploitable with sustainable techniques and locating potential sources of pollution associated with past extraction methods.

Of the 3,016 sites that have been operational in the past 150 years, only 94 currently hold valid concessions, and 76 sites were active in 2020. 562 abandoned or decommissioned mining sites present a medium to high ecological and health risk. Several museum sites have been integrated into the National Network of Mining Museums and Parks (REMI), coordinated by ISPRA.

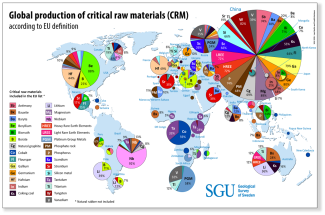

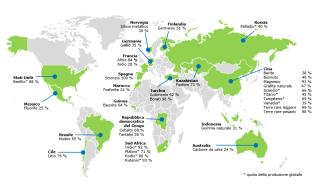

Mineral raw materials form the foundation of every civilization's development and have always directly or indirectly influenced human activities. Their importance has grown over time, becoming indispensable for technologies related to energy and vehicle decarbonization, robotics, consumer electronics, information technology, and high-tech industries (both civil and military).

Mineral resources are thus crucial for ecological transition and achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To ensure a stable supply of these materials to European industries, the European Commission launched the Raw Materials Initiative, identifying 30 Critical Raw Materials (CRMs). However, their extraction and processing, when not conducted sustainably, entail significant social and environmental costs, which are currently borne by African, South American, and Asian countries.

This indicator serves a dual function:

- Mapping the distribution of active, decommissioned, or abandoned first-category mineral extraction sites (mines), identifying exploited and potentially still exploitable mineral deposits, and providing insights into extracted mineral types and the historical evolution of mining activities in Italy.

- Highlighting potential pollution sources linked to the structure and geometry of the mined area (underground or open-pit), extraction practices, processing facilities (tailings ponds, waste dumps, etc.), and the types of extracted materials.

Currently active mines are subject to Mineral Police inspections conducted by regional authorities, often with the assistance of ARPA (Regional Environmental Protection Agencies). The major environmental challenges arise from abandoned mining sites, which—if not reclaimed—represent degraded areas with potential impacts on soil, surface, and groundwater quality.

Additional issues stem from:

- Abandoned buildings (sometimes containing asbestos)

- Dilapidated infrastructure and machinery

- Illegal waste dumping

Depending on the type of mining operation, enrichment technologies, and the geological characteristics of the ore and host rock, the degradation of extraction sites can lead to:

- Underground collapses, causing landslides and subsidence

- Surface collapses of tailings dams and waste storage sites, leading to landslides, floods, and water pollution

In metal mining operations, environmental concerns persist even after cessation if basic safety and maintenance practices for tunnels and waste storage are neglected. In Italy, these issues mainly stem from historical mining activities that lacked proper environmental protection measures.

With modern extraction technologies and continuous monitoring and regulation, mining activities can be environmentally and economically sustainable. Many mining waste deposits still contain recoverable raw materials, including CRMs, making their exploitation an example of circular economy, contributing to mineral recovery while mitigating environmental concerns.

Additionally, some closed mines—once integral to Italy's socio-economic history—have been repurposed for tourism and cultural activities.

To quantify past and present anthropogenic extraction activities for first-category minerals, which are strategically important for national industries but also have high environmental and landscape impact.

Mining sites are subject to various regulations, including:

- Royal Decree No. 1443 of 29/07/1927 (Regulation of mine exploration and exploitation)

- DPR 128/1959 (Mining and Quarrying Safety Regulations)

- Law 752/1982 (Regulation of mining policies)

- Law No. 257/1992 (Ban on asbestos extraction)

- Law No. 388/2000 (Art. 114, Paragraph 20) (Extraordinary Plan for reclamation and environmental recovery of former mining areas)

- Law 179/2002 (Art. 22) (Establishment of the Abandoned Mining Sites Inventory, compiled by ISPRA)

- Legislative Decree 117/2008, transposing Directive 2006/21/EC, regulating mining waste management

- Legislative Decree 112/1998 (Art. 34), which delegates mineral exploration and extraction permits to the Regions

- Legislative Decree 83/2012, which transfers the ownership of mainland mining sites to the Regions

- Interministerial Decree (MISE-MITE) of 15 September 2022, establishing the National Committee for Critical Raw Materials (MPC) to develop a national strategy for CRM supply, aligned with urban mining, eco-design, and sustainable mining principles

Panel 2

Carta R., Dacquino C., Di Leginio M., Fumanti F., Lettieri M.T., Lucarini M., Patanè A., Serra M., Vittori E. (2018). La banca dati Nazionale Geologico, Mineraria, Museale, Ambientale – GeMMA. Patrimonio Industriale, 17/18, 44-57. CE (2020). Resilienza delle materie prime critiche: tracciare un percorso verso una maggiore sicurezza e sostenibilità. COM(2020)474 final, Bruxelles 3.9.2020 ISPRA (2020). Viaggio nell’Italia Mineraria. Collana Pubblicazioni di pregio 2020. ISTAT (2019). Le attività estrattive da cave e miniere. Anni 2015-16. Statistiche report 15 gennaio 2019. ISTAT (2020). Le attività estrattive da cave e miniere. Anni 2017-18. Statistiche report 20 luglio 2020.

When not derived from data provided by the regions, the activity status of each site is inferred from satellite imagery, resulting in a limited degree of uncertainty. Information on the environmental status of the sites is lacking and should be obtained through greater involvement of the Regional Environmental Protection Agencies (ARPAs).

Improve data transmission by the regions.

Data quality assessment

- ISPRA

- ISTAT

- Autonomous Provinces, Regions

The basic data are derived from ISPRA’s GeMMA database, which includes data from the “Census of Abandoned Mining Sites,” the Inventory of Mining Waste Deposit Structures, the REMI network, geological mapping databases, and regional sources. These data are integrated with ISPRA analyses of satellite imagery. Production data are based on figures released by Istat for the year 2020, taken from the survey “Anthropic Pressure and Natural Risks,” available on the Istat website (http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCCV_CAVE_MIN).

National

1870–2020 (mining titles and production); 2021 (exploration permits); 2022 (extractive waste deposits)

Indicator assessment

Selection, through appropriate queries, of the sites contained in the ISPRA database of the Mining Site Census, based on spatial distribution (regions), temporal classification (cultivation period), mineralogical classification (extracted minerals), typological classification (underground, open-pit, mixed extraction), and/or any other parameter included in the database.

These statistical-environmental data have been integrated with statistical information provided by the regions, when available, and by ISTAT.

For production data, reference was made to the 2020 ISTAT data, obtained from the I.stat website.

All active concessions have been georeferenced using satellite image analysis.

There are 94 active mining concessions in the national territory, of which 76 were in production in 2020 (Table 1). The knowledge framework is considered almost complete for both decommissioned/abandoned and active activities. Active mines are significantly less impactful than old metal ore mines and generally apply sustainability criteria even in waste management, as required by current legislation. However, environmental issues related to old mining sites remain, which some regions are addressing, as evidenced by the reduction in environmentally hazardous mining sites (Table 3). The cultural importance of former mining activity in the socio-economic history of many Italian areas is indicated by the continuous increase in restored and museum-converted sites.

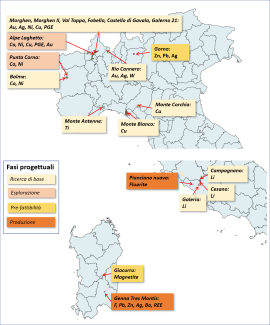

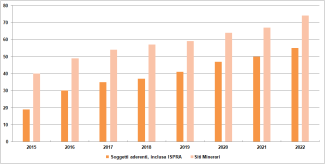

The long-standing decline in the number of mining sites continued in 2020, with a further decrease in valid concessions, contrasted by a slight recovery of operating mines (Table 1). The progress of safety procedures for waste storage structures shows that some regions have mitigated or entirely eliminated the presence of hazardous sites. There is growing activity in the recovery and enhancement of decommissioned sites (Figure 10), representing opportunities for economic and tourism development in many local areas historically tied to mining. Driven by the international political and economic context concerning raw materials, there is renewed interest in national metal mineral resources, which can now be extracted using sustainable methods, with several exploration permits being granted.

Data

Table 1: Active mining sites from 1870 to 2020, by region

ISPRA (1870–2006); ISPRA-Istat-Regions/Autonomous Provinces (2014–2020)

Table 2: National production of first category minerals (2015–2020)

Istat

Table 3: Number of sites with closed or abandoned extractive waste deposit facilities, potentially hazardous to the environment, categorized by ecological-health risk (Res) and static-structural risk (Rss) (2022)

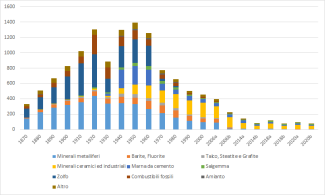

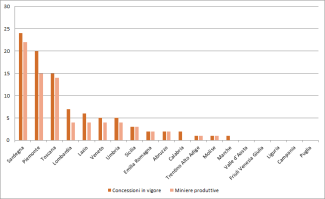

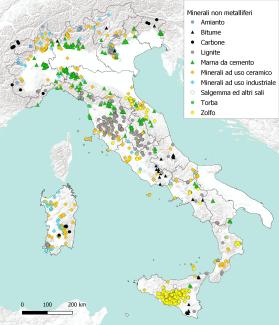

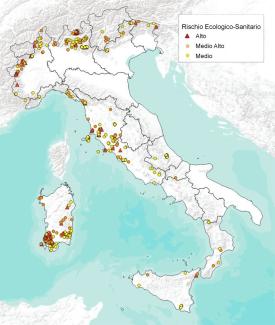

Due to its geological characteristics, Italy hosts numerous and diverse mineral deposits, spread throughout the entire territory and exploited over the past centuries, particularly since the early 20th century (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4; Tables 1, 2). Until the mid-20th century, mining activity followed a continuously increasing trend, except for a brief reversal between the late 1920s and early 1930s (coinciding with the adoption of Royal Decree 1443/1927, which regulated mining activity in Italy), before beginning to decline (Figure 1). According to the census conducted by ISPRA, 3,016 mining sites have operated on the national territory since 1870. Currently, however, the activity is virtually residual. In 2020, out of 94 mining concessions still in force, only 76 were actually in production (Table 1; Figures 1, 2, and 5), mainly in Sardinia, Piedmont, and Tuscany. The decrease in concessions compared to 2018 is due to the failure to renew or the voluntary renunciation of extraction by the concession holders. Productive activity (Table 2; Figures 1, 3, 4, and 5) is essentially linked to the presence of ceramic and industrial mineral mines (feldspar, kaolin, refractory clays, bentonite, bleaching earths), particularly widespread in the granite areas of Sardinia, and of cement marl, found along the Apennine ridge and in the Lombard-Venetian Prealps. Rock salt is extracted from the mines of the Volterra and Agrigento areas, while sea salt is obtained from the salt pans of southern Sardinia. No information is available on the salt pans in other Italian regions, which do not follow the same concession process as Sardinia. The extraction of metallic minerals is non-existent, and even the planned reopening of the lead-zinc-silver mine in Gorno (BG) was blocked during the Environmental Impact Assessment phase. Therefore, no metallic Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) are extracted in Italy. CRMs are essential elements for the European and Italian industries, but they present potential supply issues due to the geopolitical concentration of these materials (Figures 6 and 7). For metallic CRMs, Italy is entirely dependent on foreign markets, although several of them were exploited in the past within the national territory (Figure 3). The only critical material currently extracted in Italy is fluorspar (fluorite), mined in a site located in the Lazio region (Municipality of Bracciano, RM). Another fluorspar mine, after a long pause, is close to resuming operations in Sardinia (Municipality of Silius, CA). The Silius mine also contains significant quantities of rare earth elements. Due to renewed interest in mineral resources, several exploration permits are currently active for assessing the possible resumption of extraction in old metallic mineral sites, especially in the Alpine areas of Piedmont and Lombardy (Figure 9). There is also considerable interest in the potential exploitation of geothermal brines in the volcanic areas of Lazio, which are rich in lithium and other elements, with three exploration permits granted (Figure 9). Sulfur production, which characterized Sicily for centuries, ceased completely in the 1980s, and asbestos extraction was halted in the 1990s in accordance with Law No. 257/1992. Total production in 2020 (Table 2) stood at around 13.5 million tons, showing a slight decrease compared to 2018, and was almost evenly distributed across the geographic regions. Cement marl extraction predominates in central and northern Italy, while industrial minerals extraction is concentrated in the south, particularly in Sardinia. Overall, the exploitation of marl and industrial minerals represents more than 80% of national production. From the ecological-health risk perspective, currently active mines are less impactful than those for metallic minerals, whose waste contains high concentrations of pollutants. However, the issue of rehabilitating abandoned mining sites (along with their associated waste dumps and tailings ponds) remains only partially resolved. Table 3 and Figure 8 show data from the Inventory of closed or abandoned mining waste deposit structures, as required by current regulations (Legislative Decree 117/08). This inventory records sites with potential negative environmental impacts, based on the type of mined minerals and their potential waste, the size of the mining site, the duration of activity, and the time elapsed since closure or abandonment, categorized into five ecological-health risk classes (B = low risk; MB = medium-low risk; M = medium risk; MA = medium-high risk; A = high risk). The data are updated by the regions every three years, but the COVID-19 pandemic significantly slowed down regional verification activities. The number of these sites decreased from 630 in 2017 to 562 in 2022, thanks to regional rehabilitation efforts. In particular, problems were resolved for 29 sites in the Province of Trento, 10 in Tuscany, and 8 in Liguria, while the Province of Bolzano, the Aosta Valley, and Emilia-Romagna were removed from the list, having eliminated all dangerous former mining sites from their territories. The remediation of mining sites, in addition to eliminating ecological-health and structural risks, can also lead to the recovery of significant amounts of mineral resources, including many critical raw materials, still contained in extractive waste deposits. Actions in this direction are strongly encouraged by the EU as a typical example of resource circularity. Projects of this kind are being developed in Italy as well, although some regulatory obstacles still need to be overcome. Environmental restoration can also help preserve and maintain historical and social memory, particularly important in many mining areas, and can be paired with economic activities such as tourism and museum development. In this context, several mining sites have been restored and enhanced. In October 2015, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between ISPRA, MISE, the Lombardy Region, and the main Italian mining parks and museums, establishing the “National Network of Italian Mining Parks and Museums – ReMi” (Figures 10 and 11). This initiative aims to permanently connect all sites that are already working on the recovery of decommissioned mining areas, a crucial activity for the territorial, cultural, and touristic revitalization of many regions. The members of the ReMi network have increased over the years (Figure 10), from the 19 initial signatories of the protocol to the current 55, which, since a single institution can manage multiple sites, represent a total of 74 mining sites in the network. The members of the national network committee have shared the first draft of national Law No. 4566 dated 26/06/2017 on the “Protection and Enhancement of Decommissioned Mining Sites and Their Historical, Archaeological, Landscape, and Environmental Heritage,” a regulation aimed at providing a unified reference and a concrete recovery path for the most significant and valuable post-industrial mining sites in the country.